Take a Break (From Social Jet Lag)

Why do you go to sleep when you do?

Sure, there’s a big part of it that’s physical: You go to sleep because you’re sleepy. But you might also stay awake, even when you’re on the verge of collapsing from fatigue because you have work to get done. Or because your neighbor is practicing a percussion solo at 2:00 am. Or because there’s something mildly fun happening on the internet.

It’s like you’re caught in a tug of war, with your body on one side and eighteen different kinds of social pressure on the other. When your body finally triumphs and drags you into sleep, it’s winning out over incoming texts from friends, the snare drum next door, and that interesting passage in the book you’re reading. Team Body can get a boost from a stronger circadian signal for sleep, but it can also be helped along by that responsible part of our brains that tells Team Social Pressure to pack it up and go home, since “We have to get up early tomorrow, folks.”

The absence of this internal chiding is why people tend to stay up later on the weekend than on the weekdays, which shifts their circadian clock’s timekeeping, which makes it so they can’t fall asleep early enough on Sunday, which makes them end up feeling like a right proper Garfield on Monday. This is called social jet lag, and it’s been linked to lots of bad things.

But what if we had a very, very long weekend? In other words: how do we sleep when we’re on break?

I’m going to talk about this through the limited lens of a paper I was an author on in 2017, with collaborators at the University of Chicago. We looked at how people’s Twitter activity patterns changed as a function of where they were living and the time of the year. Tweeting isn’t the greatest proxy for sleep and wake, but we can at least conclude that if someone is posting a tweet, they’re probably—though not necessarily—awake.

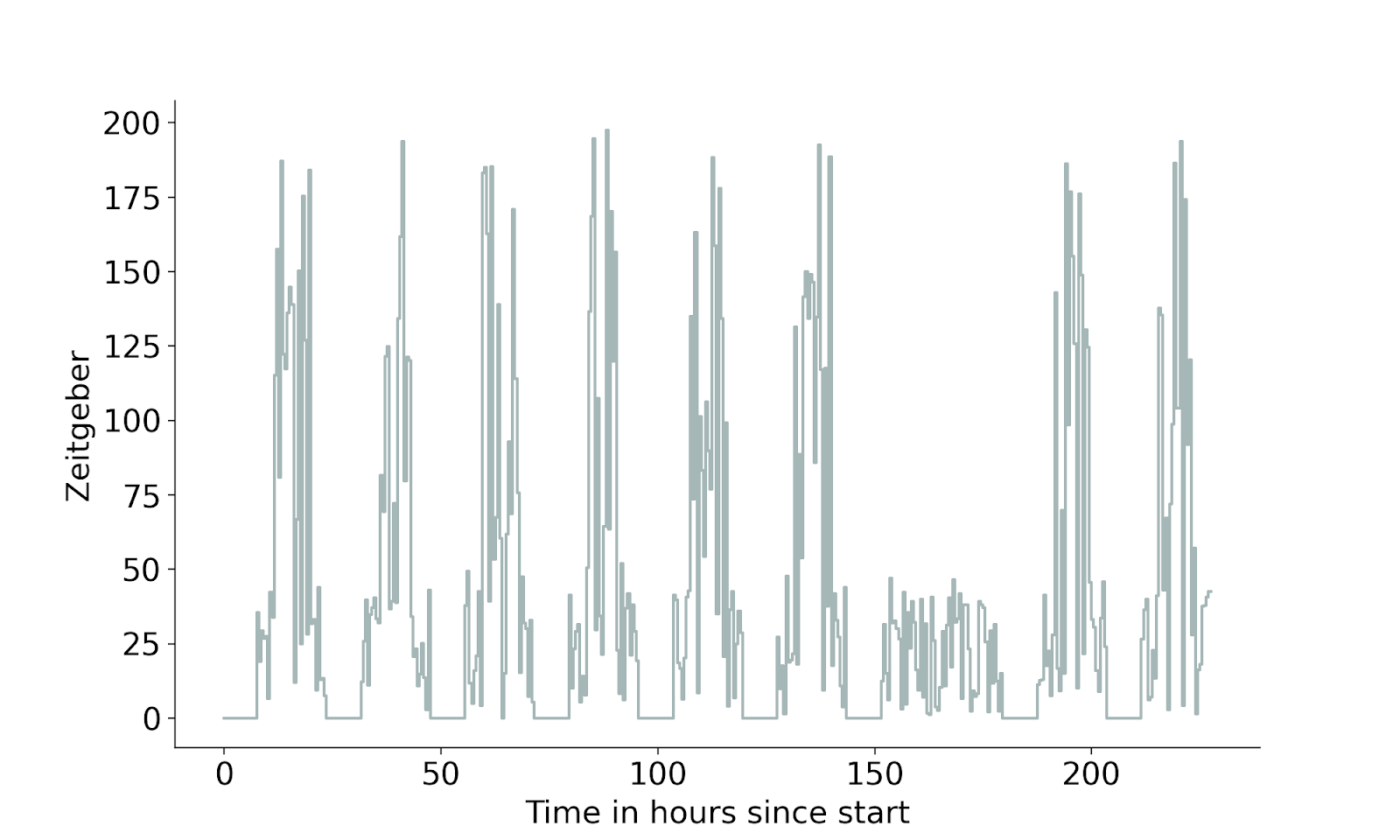

You can make plots like the below, where the blue lines show the (normalized) amount of tweets at any point in time over the course of the day, on weekdays (dark blue) versus weekends (light blue).

When the lines are low, less tweets are happening then. When the lines are high, more tweets. In the plot on the left that shows February tweeting, you can see a huge difference between weekday and weekend tweeting. In the plot on the right, for August, the minimum points for tweeting (the troughs) are nearly the same.

I remember seeing this and thinking, “Ah-ha! Seasonality effects! Human behavior is changing because the sun is changing over the year!” This, I thought, would be very interesting to report on.

Then somebody on the team (one of my brilliant co-authors), wondered if it wasn’t just that people were more likely to be on vacation in August than in February.

Reader, it was totally that.

Or, at the very least, we found some pretty compelling data to suggest that the reason why “Twitter social jet lag”— the difference between the trough in tweeting on weekends versus the weekdays— was higher in February than in August was not because of the sun being different in those two months, but people’s social responsibilities being different in those two months.

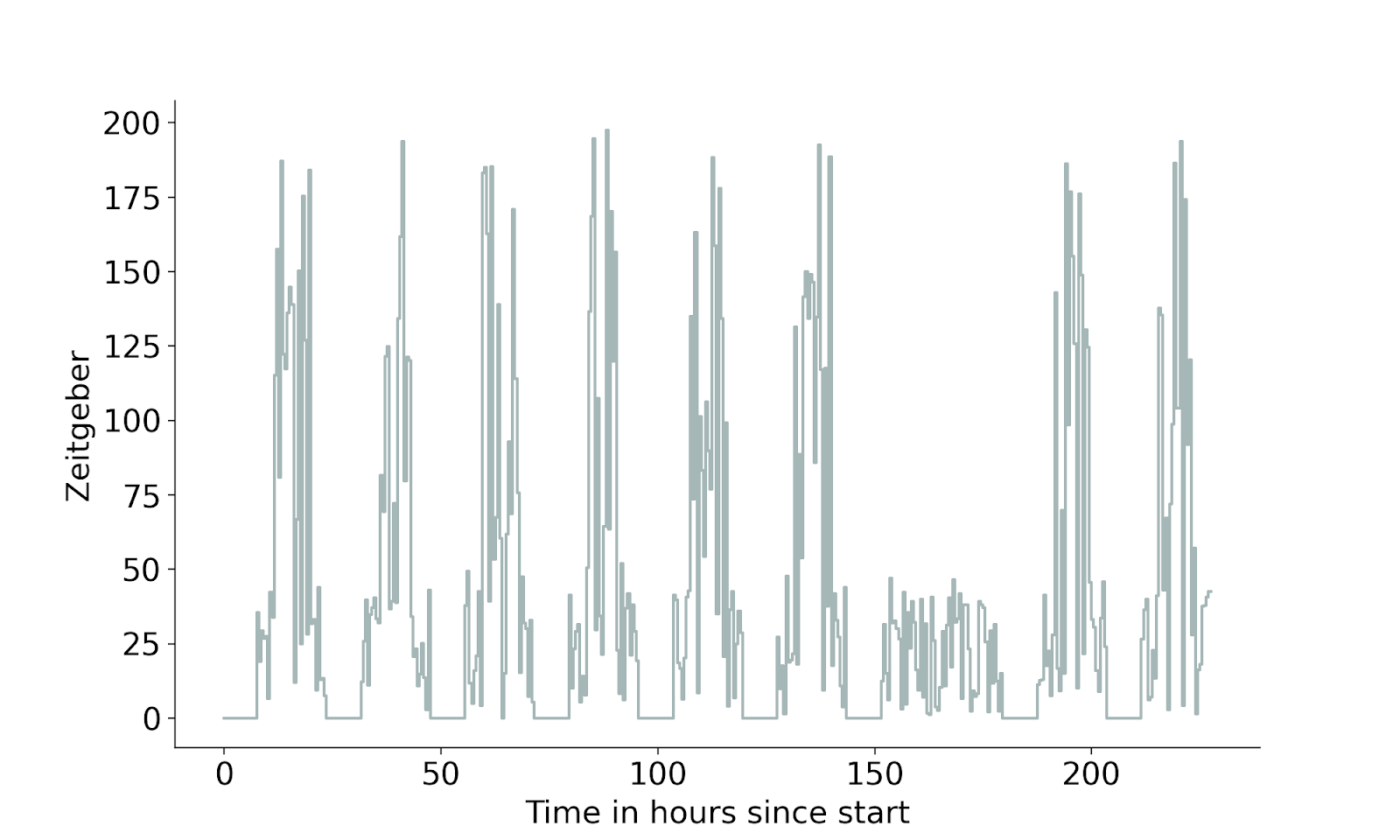

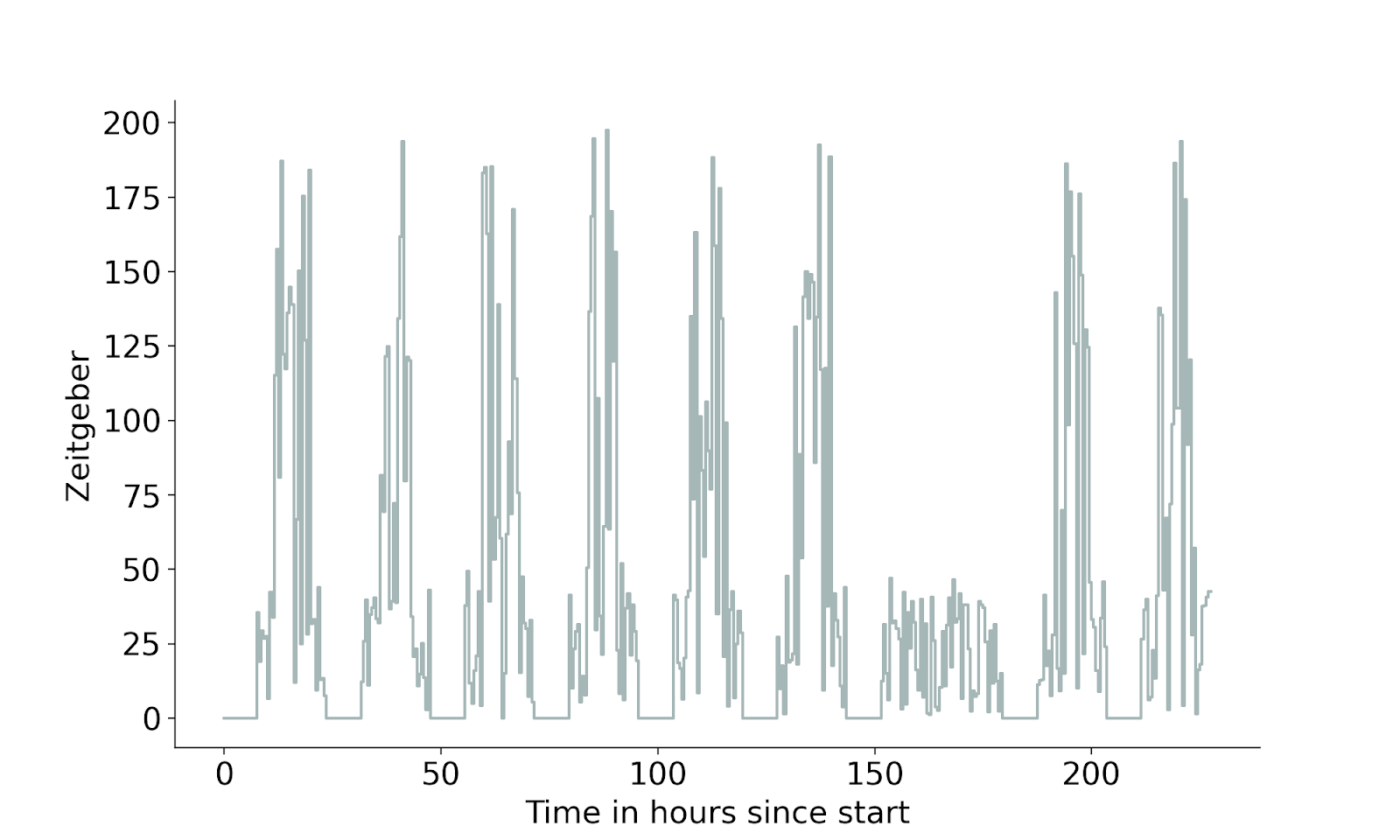

Just look at the timing of the weekday tweeting trough versus the week of the year (red line), alongside the timing of big K-12 holidays (yellow) in Orange County, FL:

Sure looks to me like every time the kids go on break, people’s tweeting activity shifts later in the day. (You see this in other counties, too).

It’s true that tweeting in 2017 might have been disproportionately done by younger people. But this still means that, according to this proxy for sleep and wake, their social jet lag was decreased. They didn’t have to get up early for school or work, so they didn’t, and there wasn’t much of a difference between their weekdays and weekends.

Which is a good thing! Don’t get me wrong: society is still set up in a way that punishes night owls more than early birds. But having your sleep be more consistent, and not jaggedly interrupted by the weekend, is healthy.

This December, as we cruise towards that glorious week between Christmas and New Year’s, the sleep of those of us on vacation time will probably shift later, like we’re in one big, endless weekend. Wednesday will look like Saturday. Sunday night and Monday morning will be no big deal.

The problem comes when we go back. Because if Twitter activity patterns are to be believed, the coming months are some of the worst in terms of “jet lagging” ourselves on the weekend.

So with the holidays coming up, take the time to rest and sleep in a nice, consistent way. Then keep it going into January. This will mean quashing down the parts of you that push for staying up late on Friday and Saturday as much as you can. But it will also mean that one of the best things about the way we seem to sleep on break will carry forward with you into the new year: better weekday-weekend sleep regularity.

Oh, and by the way: this sleep regularity? In some ways, it might even be more important to your health than sleep duration. But more on that after the break.